Scientific research has changed the world. Now it needs to change itself.

Since its birth in the 17th century, scientific theory has become a powerful idea which has been the basis for generating a vast array of new knowledge. From this, modern science has subsequently changed the world beyond recognition, and overwhelmingly for the better. However, history is also littered with scientific theories that were originally promoted as revolutionizing science only to see them eventually disappear, for one reason or other, in favour of new or modified theories.

The basis of science, of course, is: proof of any theory comes through direct observation or by direct measurement, and from this we are encouraged to: trust the work of others, but be prepared to verify. In other words, in an ideal world, scientific theories and results should always be subject to challenge from additional experiment.

It is also said that one of the very best things about science is that the discipline is self-correcting. A scientist makes a set of observations and then devises a theory to fit those observations. Other scientists then test the theory and if it withstands scrutiny it becomes widely accepted. Again, in an ideal world, at any point in the future if contravening evidence emerges the original theory may then be discarded, hence the reason why there are so many discarded theories.

Unfortunately, a successful scientific theory may also breed complacency which, over time, promotes a strong reluctance to self-correct. Because of this complacency, and the overwhelming amount of new science at our disposal, modern scientists are now doing too much trusting and not enough verifying, in particular testing the fundamental assumptions upon which a theory was originally based? If taken too far, this trust and complacency can then be to the detriment of the whole of science, and of humanity.

What a load of rubbish

That is how science is supposed to work and no doubt, in most cases, still does but in practice it is often much more complicated. Chalk it up to humanity’s collectively huge ego but, the classic example of complacency taken to the extreme was Ptolemy’s Earth-centred model of the Solar System. Because of pious religious insistence this model of the Solar System remained intact for 1,500 years. The model lasted for so long because of a single, uncontested assumption: that the Earth, and hence man, was located at the centre of the known universe and therefore everything else must revolve around the Earth. Any attempt to contest this assumption was condemned by the church and the model remained intact until Copernicus published his Sun-centred heliocentric model in 1543. Copernicus wasn’t the first to suggest that we orbit the Sun, but his theory was the first to gain traction and eventually reset the course of scientific history.

Ptolemy’s Earth-centred model was able to survive for so long because, over time, auxiliary hypotheses, also referred to as ad hoc hypotheses, were added to the original model in order to both incorporate new observations and to save the model from being falsified. Ad hoc hypothesizing is a way of compensating for anomalies not anticipated by the theory in its unmodified form. While scientists are often sceptical of ad hoc hypotheses that rely on frequent unsupported adjustments to sustain the primary theory, there is no limit to the number of hypotheses that they could add. Thus, a particular theory runs the risk of becoming more and more complex, but without viable alternatives it is never falsified, even at a cost to the theory’s credibility and predictive power.

We have now become accustomed to thinking that this could never happen to us and modern science thinks it has overcome the possibility of a reoccurrence of this Ptolemaic dilemma, but this is not necessarily so. One reason for this thinking is the competitiveness of modern science and the complacency of modern mass media. Science is supposedly self-correcting but mass media is not.

In the 1950s, when modern academic research began to take shape, science was still a rarefied pastime. The entire club of scientists numbered a few hundred thousand. As their ranks have swelled, scientists have since lost their taste for self-policing and quality control. The obligation to publish or perish has come to rule academic life. Nowadays, verification or replication of other people’s results does little to advance a researcher’s career. And without verification, dubious findings may remain in place to potentially mislead all that follow.

Careerism also encourages exaggeration of results. In order to safeguard their exclusivity many leading journals impose high rejection rates, often in excess of 90% of submitted manuscripts. The most striking findings, often simply masquerading as ad hoc hypotheses, therefore have the greatest chance of making it into publication. Little wonder that pepping up a paper by, say, excluding inconvenient data from results based on a gut feeling all too often happens. And as more research teams from around the world work on a problem, the odds shorten that at least one will fall prey to an honest confusion between genuine discovery and a freak of statistical noise.

Conversely, failure to prove a hypothesis is rarely offered for publication, let alone accepted. Research sponsors do not fund science projects or theories that fail or have been rejected. Yet, knowing what is false is just as important to science as knowing what is true. This failure to report failures means that researchers may then waste time, money, and effort unknowingly exploring avenues already investigated by other scientists.

All this makes a shaky foundation for an enterprise dedicated to discovering the truth about the world. Science still commands enormous—if sometimes bemused—respect but its privileged status is founded on the capacity to be right most of the time and to correct its mistakes when it gets things wrong. And it is not as if the universe is short of genuine mysteries to keep generations of scientists hard at work. The false trails laid down by shoddy, untested research can, of course, be an unforgivable barrier to ongoing research and understanding.

Superseded scientific theories

In order to work, most scientific theories are based on some form of assumption, or set of assumptions. An assumption is a proposition that is accepted as true in order to provide a basis for logical reasoning: something that you assume to be true, even without proof, from which a conclusion can be drawn. These assumptions are necessary in order to overcome any limitations to the concepts or ideas that were not fully understood at the time the theory was first proposed or promoted.

Over time, true science insists that we must then continually challenge these assumptions until such time as the original concepts and ideas are fully understood and can be confidently accepted within the discipline as truth. If time shows that these basic assumptions are incorrect, true science also insists that the particular theory, or discipline being promoted must either be modified or rejected in favour of a theory that better suites the available evidence.

From this, established theories then become superseded over time, not necessarily because the theory was wrong, but because the assumption that formed the basis for the original theory may have been wholly, or partly, wrong. If the primary assumptions on which the discoveries or theory were based remain untested, then no amount of change or replacement will alleviate the fact that the primary assumptions may still be wrong.

Premature rejection

Before plate tectonics was introduced in the mid-1960s, a number of scientists actively promoted the alternative theory that the Earth is steadily increasing in radius. This was promoted in the days of free scientific thinking, well before the advent of so called modern science, mass media, and the instigation of a narrow-minded peer review system to safeguard science.

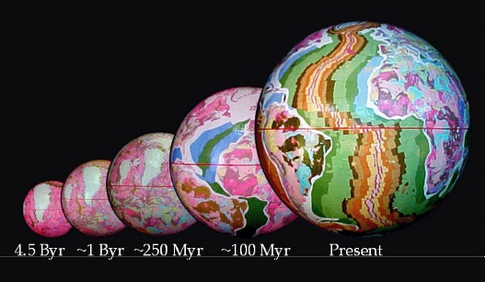

The expanding Earth theory basically maintains that Earth radius is increasing with time and 250 million years ago all existing continental crusts were assembled together to cover the entire ancient Earth at a much smaller radius. At the time of this proposal scientists had only just accepted the fact that continental crusts could move across the face of the Earth—then called continental drift. Earth expansion theory was unceremoniously rejected during the 1960s in favour of the static Earth radius plate tectonic theory, not because the theory didn’t work but because, at the time, scientists could not comprehend how Earth radius could possibly increase.

In practice, the theory of Earth expansion has indeed been adequately rejected to the satisfaction of a scientific community constrained by a constant radius Earth pre-conception. But, the expanding Earth theory has never been proven wrong exactly. In case you missed the subtlety of this statement I’ll say it again. The expanding Earth theory has never been proven wrong exactly, it has simply been replaced by the seemingly more sophisticated theory of plate tectonics. In addition, the expanding Earth theory has never been tested using modern global tectonic data. Rejection is based almost solely on data and opinions from half a century ago.

As previously stated, if the primary assumptions on which discoveries or theories are based on remain untested, then no amount of change or replacement will alleviate the fact that the primary assumptions may still be wrong. Hence, the theory of Earth expansion may have indeed been prematurely rejected.

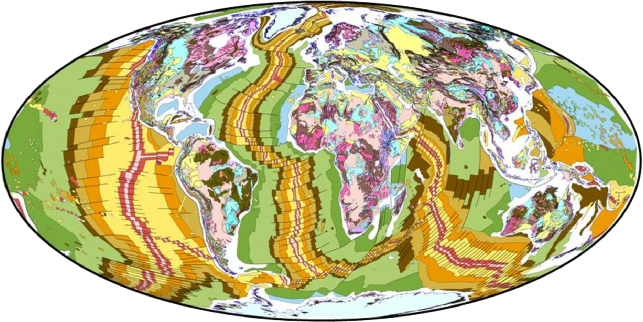

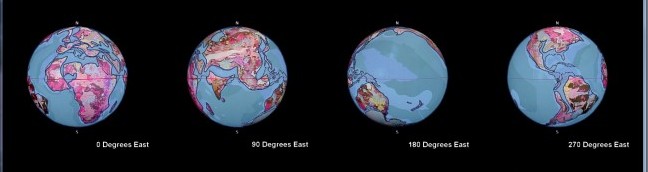

The fundamental difference between plate tectonic theory and what is now known as Expansion Tectonic theory is that plate tectonics insists that the radius of the Earth has remained essentially constant throughout all time. Hence, in plate tectonic theory all gathered global tectonic data is constrained to a constant radius Earth model. In contrast, Expansion Tectonics simply removes this fundamental insistence and allows Earth radius to change with time. The same global tectonic data displayed on an Expansion Tectonic Earth then remains unconstrained from any preconceived assumptions.

The moral of this story is to acknowledge that, throughout history, science often gets it wrong but sometimes we become so complacent that, thanks to the well-meaning peer review system, we cannot accept being wrong. If we can believe in the well-intentioned merits of modern science i.e. founded on the capacity to be right most of the time and to correct its mistakes when it gets things wrong then surely it is time to reconsider, re-evaluate, revise, or reject outdated theories such as plate tectonics.

In modern science, it would seem that error is better than confusion.

For more information on Expansion Tectonics see: www.expansiontectonics.com